Writing Comics 101

Someone said to me at the very beginning of my comic book career that “everyone wants to be a comic book writer.” That’s not too far from the truth. Oftentimes when being interviewed or meeting people at signings and conventions, I’m asked how to make a comic. It’s a loaded question that isn’t easy to answer. I direct them to the internet (obviously), how-to books, video tutorials, and other great references. However, with so much information out there, I thought it would be helpful to provide basic fundamentals that anyone can take and build upon if they want to tackle writing in this extremely unique medium.

First, I suggest beginning with brainstorming (also known as “pre-writing”) to get all of your ideas out of your head and on paper. And, yes, I recommend actually writing them down on good old-fashioned paper. I find this method really helps me to get loose and not so formal too early in the writing process. At this stage, you shouldn’t need to worry about spelling, grammar, punctuation, and other nuances that can be fine-tuned down the road. Write down your title in several different ways (i.e. add a “The” or spell it differently). List your characters and their main traits. Jot down the locations that will be visited. Outline the main events that will occur across the entire story. Most of all, don’t worry about whether it makes sense right now. Just get it down in a tangible notebook that you can refer to at a later date. Your future self will be grateful!

Next, work on your “elevator pitch.” This should be a short one or two sentences that hook a potential reader. Imagine you’re riding on an elevator with a stranger, and you only have a few floors to explain what your comic book is about. You’re going to need to have this committed to memory as it will be something you will use long after your comic book is complete. A good example of an elevator pitch is the tagline you might find on movie posters. It has to be something intriguing and unique but quick enough to read for the below-average attention spans. Once you think you have your elevator pitch, practice saying it out loud. You should be able to verbalize it organically with a fluid, professional cadence that gives people confidence in your creation.

At this point, you should be able to begin working on your comic book’s script. I like to describe the format as similar to a play or movie script with some slight variations. There are no hard guidelines to follow, but you will need to describe the art direction (what’s happening in each panel) and the dialogue (i.e. word balloons) that will appear on every page. This is what sets comic books apart from novels. You can find plenty of great script examples online for free by doing a simple Google search. If you want to dive deeper, a few books I’d recommend getting your hands on are:

- Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels by Scott McLoud

- The Art of Comic Book Writing: The Definitive Guide to Outlining, Scripting, and Pitching Your Sequential Art Stories by Mark Kneece

- Comics Experience Guide to Writing Comics: Scripting Your Story Ideas from Start to Finish by Andy Schmidt

I was able to borrow each of these from my local library, and there are used copies available on Amazon.

Now that you have your script, it’s a good time to look into hiring an editor. Despite how awesome you think you might be at spelling and punctuation, it would behoove you to get another pair of eyes, specifically an experienced set, to review your writing. This isn’t only to proofread your material but also to make sure the story will flow in an appropriate manner. Remember that this story has been living rent-free in your head for however long you’ve been contemplating the idea. It makes sense to you, but what about someone else who just opened the comic book to page one? An editor will provide suggestions with the intent to improve your script. Plus, they should also be with you for all stages of the comic book. So they’ll review the artwork, colors, and lettering as those roll in during the project’s life. The best part, you only have to agree to the changes that you want. At the end of the day, it’s your baby, and you don’t have to change anything. Just try to explain to your editor why you’re standing firm on something so they can understand your decision. This makes for a better working relationship.

Finally, you’ll need to hire an artist, colorist, and letterer (unless you plan to do any of those tasks yourself). This step in creating your comic book can produce a lot of anxiety. You want to verify that whoever you hire is not only fit for your project but reliable and trustworthy. There are a lot of scammers out there who would love nothing more than to take your money and never communicate with you again. On the flip side, there are also plenty of professional creators who are eager to collaborate. The challenge is knowing the difference. A good way to determine if an artist, colorist, or letterer won’t steal your money is to ask someone for recommendations. If you know another comic book creator, ask them who they have worked with before and would hire again. Then, when you contact a potential hire, discuss the details of your project with them so they know it’s a good fit for them. For example, if your comic book will be a multi-issue run, check with them that they can stay on for the full series. If not, maybe they’re better suited for a one-shot project.

As I mentioned before, there’s nothing set in stone on how to make a comic book, and these steps don’t necessarily have to be followed in this order or at all. What I presented here are merely some suggestions from my own experience. I hope at the very least it provides you with some direction to get started on your own comic book project. I’m excited to see what you create!

About the Author

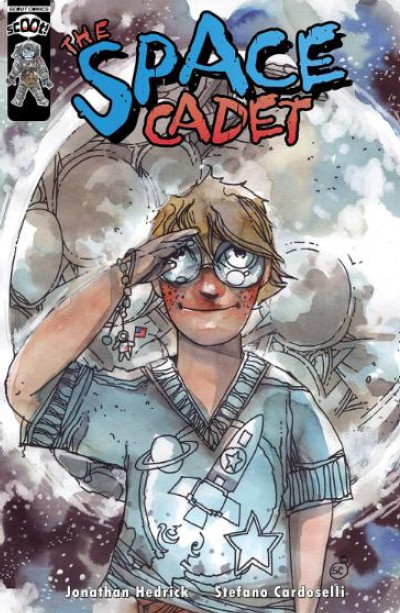

Jonathan Hedrick is a multi-published independent comic book writer from Central Florida. His creator-owned titles include The Recount (Scout Comics), Space Cadet (Scoot!), Hyper/Aware (Source Point Press), Caffeinated Hearts (Source Point Press), and Freakshow Knight (Second Sight Publishing). He has also contributed to several anthologies, most recently Lower Your Sights (Mad Cave Studios), which raised support for children impacted by the war in Ukraine. He currently writes Dream Master for BlackBox Comics. His latest titles, Capable (Advent Comics) and Quicksand (Scout Comics), can be found at your local comic shop. He lives with his wife, Francesca Fantini, and their two fur-babies, Tessa and Akita.