By Mike Wheeler

In an industry built on imagination and original art, few offenses irk comic book creators and fans more than straight-up copying another artist’s work.

Recent years have seen multiple high-profile cases of artists being accused of tracing or closely referencing the work of others without permission or proper attribution. Critics say the practice deceives readers and amounts to artistic plagiarism. Where some see a harmless shortcut, others see an ethical lapse and betrayal of the comic medium. “It’s about respect – respect for your colleagues in the industry and respect for the readers who are paying for authentic art,” said comic artist David Smith, who has spoken out against tracing. “Just like with plagiarism in writing, outright copying with minimal changes is seen as theft in the comics world.”

The most common form involves an artist projecting or overlaying the original image while drawing their own version. Sometimes only a portion of the comic panel is traced; other times, the entire image is a near carbon-copy of the source material with minor alterations.

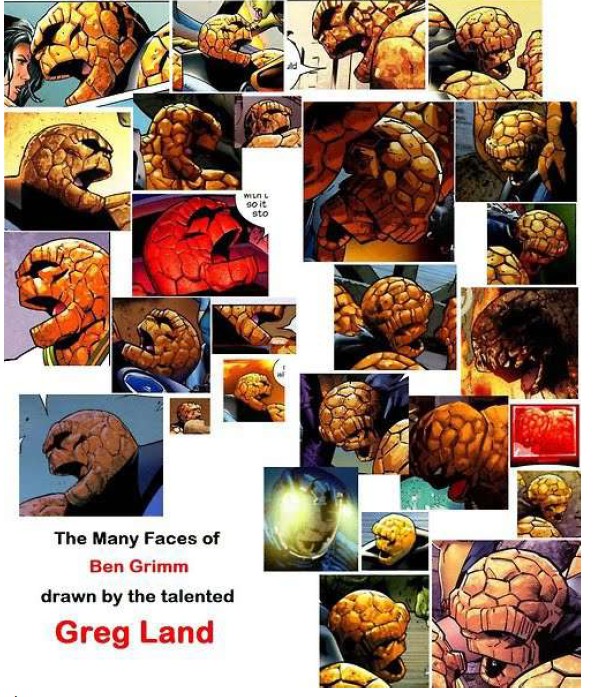

Longtime comic book artist Greg Land has faced constant criticism for allegedly tracing photographs, movie stills, and the work of other artists for decades. Greg Land has responded to criticism by stating that he uses extensive photo reference to achieve lifelike realism in his comic art. Fellow artists counter that Land’s work copies the exact poses and lighting of reference photos rather than using them as inspiration.

In the 1990s, artist Rob Liefeld was accused of extensive swiping from legends like Jack Kirby. Liefeld’s reputation suffered major damage when panels he drew for X-Force and Captain America were exposed as near-identical replicas of work by esteemed artists like Jack Kirby and Walt Simonson. Liefeld defended his actions as an homage, but later admitted to using tracing as an artistic shortcut early in his career.

More recently, colorist Chris Sotomayor admitted to referencing movie stills for some Marvel projects, reigniting debate in the community about what constitutes ethical vs. unethical referencing. In 2017, colorist Chris Sotomayor wrote on social media that he “strongly disagreed” with assertions that his process amounted to tracing. He explained that he projected movie stills at low opacity while coloring to help match the realistic lighting of live-action films.

Marvel confronted artist Milo Manara after internet sleuths revealed he copied numerous paintings by Frank Frazetta for X-Men comic covers in the early 2000s. Manara apologized for deceiving fans and said he became “carried away” trying to pay tribute to Frazetta’s style.

Neal Gaiman admitted to referencing some character sketches by John Byrne early in his comic writing career after Byrne publicly accused him of more extensive tracing. Gaiman called it a “learning experience” and said he quickly realized copying was wrong as he developed his own recognizable style.

While comic stalwarts argue any tracing at all is off-limits, some defend light referencing as a learning tool or say the main criteria should be properly crediting the original artist. All seem to agree that totally copying major elements crosses the line. As artist David Ross put it: “Using photo reference or taking inspiration from others’ styles is fine and encouraged. But if you try to pass off whole panels or characters that you didn’t create yourself, that’s when you’ve crossed over into shady territory.”

“Tracing undermines the unique magic of comics – that artists can conjure up entire worlds from their imagination,” said comic book reviewer Valerie Lane. “It deceives readers who assume they’re seeing an artist’s original vision.”

But for many purist comic artists, the solution is simple – put in the hard work to develop your own style rather than piggybacking off the talent of others. As comic legend Stan Lee often said: “Keep your pencil moving, and your brain always thinking.”

Meanwhile, artists accused of tracing often downplay the practice as exaggerated or claim their imitations fall within creative license. The rise of digital art and the ability to easily overlay reference images has made tracing temptations even greater today. Some experts argue that clearer ethical guidelines are needed in the internet age. There are also calls for publishers and comic companies to do more policing for such practices.

The most recent case of this stems from a piece of a comic book character “Rogue” in 2021. Some of what looks to be some of the exact linework is used in a piece drawn by Jamie Tyndall in 2023 for an Indie comic called Nyobi. Nyobi is currently being published by Antarctic Press. Comics Illustrated reached out for comment from Brett Booth about this situation. We asked, “We are going to be running a story on professional ethics when it comes to doing homages or cover swipes. With the closeness in this piece, do you see anything that you would consider to be out of line? There was no ‘After Booth’ credit or homage credit by the way.” Brett replied, “Yeah, you don’t trace others’ work. You can trace pictures you take yourself, but to me, doing it this way, would be unethical. At least that’s what I was taught. Would have been less noticeable if they just redrew it.”

Next, we approached the publisher Antarctic Press. “We will be running a story in regards to comic book professional ethics. We would like to request from you a comment in regards to one of the books you currently publish and have your company’s name on. It seems that one of your series, Nyobi, by Larry Higgins, has a variant cover from Jamie Tyndall that looks as if it could be traced or copied close enough to constitute theft from another major artist, namely Brett Booth. What is your company’s position on art theft?” Antarctic Press responded, “You can reach out to Larry Higgins on Facebook, who created the Nyobi book and has a YouTube channel as well.” We say, “We are aware that we can reach out to Mr. Higgins, however, as his publisher on record, we are requesting a comment from you. Or would you like your deflection to Mr. Higgins to be the comment of record?” The message was read, but not responded to. So we proceeded to ask more follow-up questions. “Do you have any policies in place for situations like this? Do you have a contract between yourself and the creator with a hold harmless agreement in regards to intellectual theft and/or theft of art? Do you have a disciplinary or review procedure when an accusation like this is made? Being that your stance on what seems to be art theft is no stance, what kind of message do you think that sends to other creators who might be thinking of using you as a publisher?” These messages were read, but Antarctic Press had no response.

While the ethical lines remain blurry, some high-profile cases have sparked more concrete fallout. While no legal action has been taken, the court of public opinion often delivers harsh judgments against artists perceived to have crossed ethical lines. Many see traceback as a painful but necessary self-correction for an industry built on originality and imagination. As comic patron Orson Clarke commented: “The only way to steer things back on track is to call out inappropriate behavior when we see it. That’s how all fields stay on the up and up.” In sum, the consensus seems clear – directly copying others’ work without permission will only stifle an artist, while developing one’s own vision will let every comic creator soar.

The rampant tracing accusations have fueled a broader debate about establishing ethical guidelines for the comic industry. While explicit plagiarism is universally condemned, standards grow murkier for “swiping” versus direct copying, mashing up multiple references, or artists building upon each other’s styles.

“The comic world today involves so much cross-pollination of ideas and imagery. We need better definitions of what’s totally off-limits versus a gray area,” said artist and advocate Tina Sanders.

Publishers have shied away from overtly policing their artists for tracing. Some say independent consumer watchdog groups may be better suited for investigating and exposing comic art infractions. Others argue true change must come from artists themselves ceasing unacceptable practices, not just avoiding getting caught. But veteran creators admit the career pressure to produce monthly books often pushes artists toward shortcuts.

“Pencilling a full comic is gruelling work. I understand how tight deadlines can sway someone’s ethics,” said acclaimed comic artist Leo Trent. “But we must find a way to remove those temptations.” Proposed safeguards include artists publicly listing full photo references, studios implementing plagiarism-detection software, and companies enabling pencilers to take more time per page. But Trent and others stress that real change requires a commitment from artists to do the painstaking work of building their talents rather than copying from others. “It’s about having pride in your craft,” Trent said. “That’s what every creative field demands. And that pride is what will elevate comic art to even greater heights.”

Tracing is called out or overlooked depending upon how the artist’s participation affects sales and popularity, full stop. Greg Land still gets work. What really jumps out to me is situations where tracing is not talked about because the creator has a larger influence outside of the publication. Tula founded Thought Bubble Festival. Wanna never get invited to Thought Bubble again? Mention Tula’s tracing.